Surrogacy is a method of assisted reproduction where a woman agrees to carry and deliver a child for another person or couple, known as the intended parents. It offers a lifeline to individuals who, for medical reasons, are unable to conceive or carry a pregnancy to term. Increasingly, even women capable of carrying their own pregnancies are turning to surrogacy as a matter of personal choice and convenience.

Globally, jurisdictions such as the United States, Australia, Canada, and South Africa have recognized the evolving dynamics around parenthood and codified surrogacy into law. These legal frameworks have created structured, predictable, and secure environments where intended parents and surrogate mothers can engage in well-defined, enforceable arrangements.

In contrast, Kenya finds itself at a crossroads. While surrogacy is not explicitly outlawed, it exists in a legal vacuum—unregulated, undefined, and largely misunderstood. The law has not kept pace with scientific advancements in reproductive health, leaving families, surrogates and professionals navigating murky and uncertain terrain.

The consequences of this legislative silence are far-reaching. With no statute specifically governing surrogacy, intended parents enter into private arrangements with no legal safety net. If a surrogate mother chooses to keep the child or refuses to relinquish custody after birth, the intended parents may find themselves with no legal recourse despite the child being biologically theirs. What should be a joyous journey to parenthood becomes a stressful, emotionally taxing gamble.

Even more troubling is the absence of regulation for surrogacy agencies in Kenya. These agencies are often the initial point of contact between potential surrogates and hopeful parents but without oversight, they operate in an informal and often careless manner. Many do not conduct proper screenings or assessments to determine the psychological, medical, or social suitability of surrogate mothers. This oversight gap has in some cases led to devastating outcomes such as pregnancies terminated midway, unsafe lifestyle choices by surrogates, or complete breakdowns in the arrangement due to hostility or non-cooperation.

One of the most paradoxical aspects of this unregulated landscape is the legal treatment of the child once born. In many cases, intended parents are compelled to adopt their own biological children. This legal irony, where a couple must legally "apply" for the very child genetically tied to them, underscores the urgent need for reform.

Efforts to address these issues have been made. In 2019, the Reproductive Healthcare Bill was tabled in Parliament with provisions aimed at regulating surrogacy. However, six years on, the Bill has yet to be enacted, stalled in the corridors of Parliament. The lack of political will and legislative urgency continues to expose countless families to unnecessary legal and emotional distress.

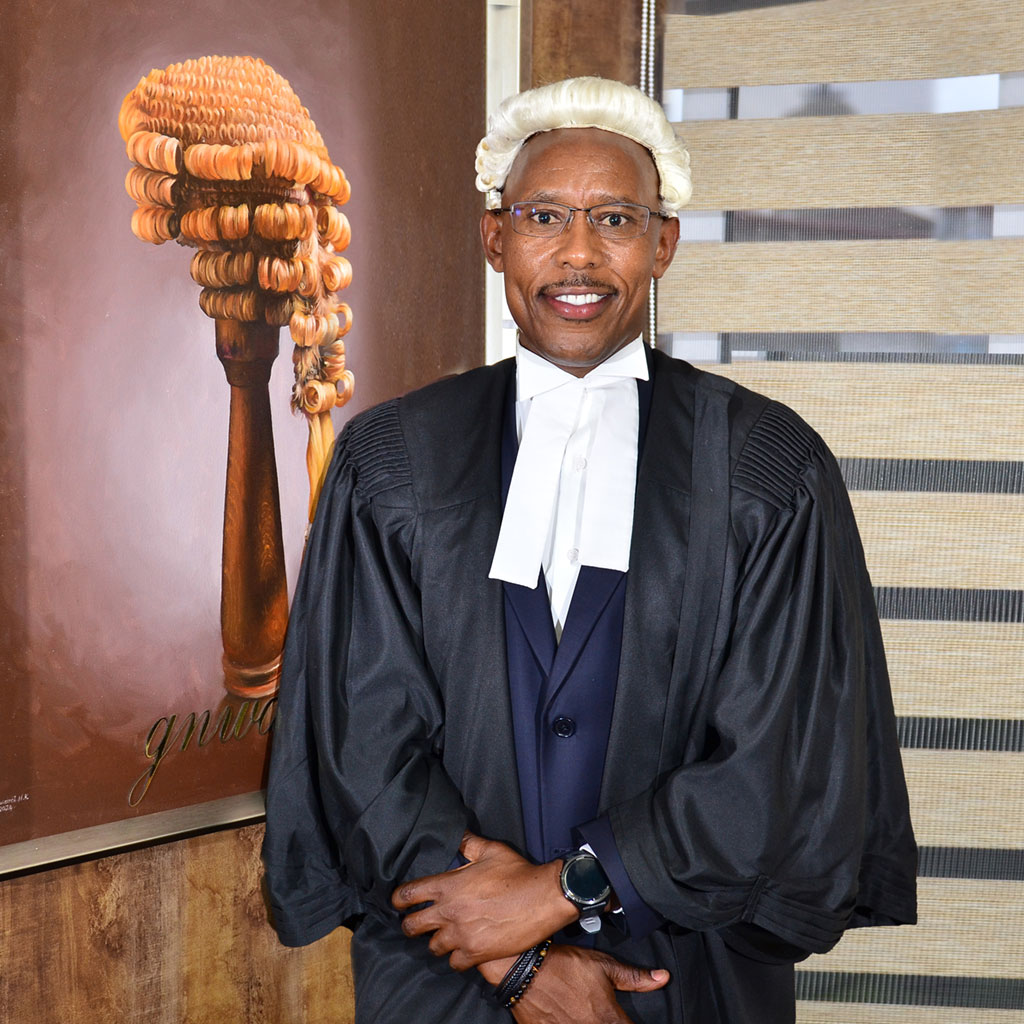

In the meantime, one of the most effective ways for intended parents to safeguard their interests is to engage experienced legal counsel. Lawyers well-versed in the intricacies of surrogacy can guide clients through the process from drafting comprehensive agreements to navigating court procedures and safeguarding custody rights. Their expertise becomes invaluable in mitigating risk, anticipating complications and ensuring that every step of the journey is as secure and predictable as possible.

Surrogacy in Kenya holds immense promise. It is a powerful tool of hope for families unable to conceive or carry children. But until the law catches up with reality, intended parents must tread carefully. Legal guidance is not just advisable—it is essential.