“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” Benjamin Franklin

Advocates play an indispensable role in land-related transactions, ensuring legal compliance, protecting parties from fraud and safeguarding property rights. So significant is this role that the Court of Appeal in National Bank of Kenya Ltd. v. Wilson Ndolo Ayah [2009] eKLR held that the Advocates Act mandates that conveyancing documents be prepared exclusively by qualified advocates. Although this position was later overturned by the Supreme Court in National Bank of Kenya Limited v. Anaj Warehousing Limited [2015] eKLR, the Supreme Court did not diminish the necessity of legal expertise in land transactions.

In fact, while the Supreme Court departed from the Court of Appeal’s strict requirement, it re-affirmed the critical importance of engaging qualified legal professionals. The Court expressly held that “…documents prepared by other categories of unqualified persons, such as non-advocates, or advocates whose names have been struck off the roll of advocates, shall be void for all purposes.” This pronouncement underscores that while conveyancing may not be exclusively reserved for advocates, transactions conducted without proper legal oversight remain vulnerable to invalidation, disputes, and legal risks.

The role of the Advocate in land transactions has evolved significantly, shifting from a traditional focus on drafting and processing documentation to a more investigative function, a significant shift from the Torrens Land System. Under this system, which Kenya subscribes to, records maintained by the Lands Registry are presumed to be conclusive evidence of ownership and the sanctity of a title. Section 26 of the Land Registration Act underscores this system by providing that a Certificate of Title issued by the Registrar, whether upon registration or to a purchaser following a transfer or transmission, shall be taken as prima facie evidence that the person named therein is the absolute and indefeasible owner of the land, subject only to any registered encumbrances.

However, this presumption is not absolute. The same section allows for the impeachment of title on limited grounds: - namely, where the certificate was obtained through fraud or misrepresentation in which the titleholder is proven to have participated, or where the title was acquired illegally, unprocedurally, or through a corrupt scheme.

However, recent jurisprudence, particularly from the Supreme Court, held and emphasized that the sanctity of title does not rest solely on compliance with sections 24, 25, and 26 of the Act which speak registration and its effect. Rather, the validity of any title is ultimately anchored in the integrity of its root. If the foundational title from which a current title derives is found to be defective or fraudulently acquired, then even an innocent purchaser for value without notice may lose their title. In such circumstances, it is immaterial that the title was formally registered under the Land Registration Act.

In Dina Management Limited v County Government of Mombasa & 5 others (Petition 8 (E010) of 2021) [2022] KESC 24 (KLR) (Civ) (19 May 2022) (Ruling), the Supreme Court held as follows: -

“To establish whether the appellant is a bona fide purchaser for value therefore, we must first go to the root of the title, right from the first allotment, as this is the bone of contention in this matter…………………Article 40 of the Constitution entitles every person to the right to property, subject to the limitations set out therein. Article 40(6) limits the rights as not extending them to any property that has been found to have been unlawfully acquired. Having found that the 1st registered owner did not acquire title regularly, the ownership of the suit property by the appellant thereafter cannot therefore be protected under Article 40 of the Constitution. The root of the title having been challenged, as we already noted above the appellant could not benefit from the doctrine of bona fide purchaser.”

The Supreme Court in the above case also cited with approval the Court of Appeal’s decision in Munyu Maina v Hiram Gathiha Maina Civil Appeal No. 239 of 2009 [2013] eKLR that: -

“…where the registered proprietor’s root title is under challenge, it is not enough to dangle the instrument of title as proof of ownership. It is the instrument that is in challenge and therefore the registered proprietor must go beyond the instrument and prove the legality of the title and show that the acquisition was legal, formal and free from any encumbrance including interests which would not be noted in the register.”

In light of this jurisprudential shift, Advocates are now expected to go beyond basic registry searches. They must thoroughly investigate the root of title, including the first registration and the history and legality of all subsequent dealings, transfers, transmissions, or otherwise. This enhanced due diligence is essential to ensure that their clients acquire a valid and indefeasible title, and to safeguard against the risk of a bona fide purchaser’s rights being defeated by defects in the chain of title.

Given the complexities of land law and the high incidence of fraud in property transactions, involving an advocate is not just a legal formality, it is a crucial safeguard against costly legal pitfalls.

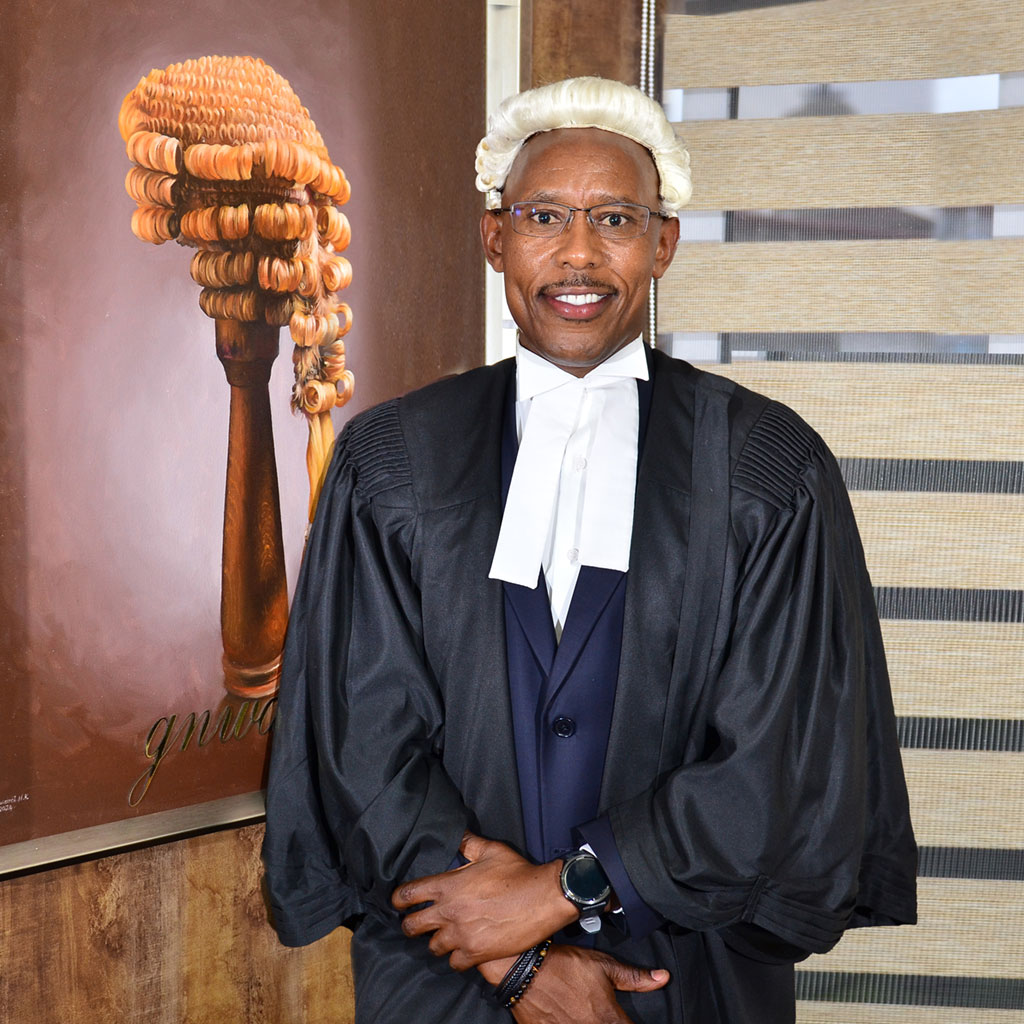

By George Ng’ang’a Mbugua & Jude O. Orenge